The Father of Japanese Folklore Studies

Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962), known as the “father of Japanese folklore studies,” was a multifaceted intellectual who pursued a complex career as a bureaucrat in the Japanese government, a scholar, and most importantly, a folklorist.

He was born in Hyōgo Prefecture in western Japan, where he lived until he was eleven years old. At twelve, he moved to Ibaraki Prefecture, not far from Tokyo, where he witnessed the lives of common people facing the challenges of poverty.

After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University with a law degree in 1900, he began his career as a civil servant in the Department of Agricultural Administration at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce.

Yanagita traveled extensively in rural Japan, recording and analyzing local customs, practices, beliefs, and cultural objects. Encouraged by his friends in the field, Yanagita began to publish his works, often including compilations of field notes on folktales and oral traditions with particular interest in impoverished areas.

Major Works

The following three works by Yanagita are particularly well known. The first, The Legends of Tōno, brings into focus the everyday lives of commoners in a poor community in northeastern Japan. The second, A Study of the Word Snail, examines the gradual changes that take place in language and culture. The third, The Roads on the Sea, observes the hybrid nature of Japanese culture and suggests that rice-growing practices and the culture built around them were brought from the south.

The Legends of Tōno [Tōno-monogatari] (1910): This is a well-known collection of folk legends, stories, and traditions from Tōno village, a small community in the mountainous region of Iwate Prefecture in northeastern Japan. Yanagita visited the village and recorded the stories as they were being told, namely, as part of an ongoing contemporary storytelling.

A Study of the Word Snail [Kagyūkō] (1930): This work focuses on the center versus periphery hypothesis of language diffusion, according to which words spread from influential centers of culture outward to remoter peripheral regions over time. The word for snail in Japanese varies greatly across Japan and is taken as a paradigmatic example to support the hypothesis. Based on historical records and fieldwork, Yanagita illustrates how the word for snail spread from the Kyoto area to other parts of Japan.

The Roads on the Sea [Kaijō-no-michi] (1961): Yanagita hypothesized that the Japanese people came from the far south along the sea route northward to the island of Okinawa with rice cultivation skills and then moved further to mainland Japan. In Yanagita’s view, this explains the presence of southern elements in Japanese culture. He thinks the Japanese archipelago has been connected to the wider world through maritime routes since ancient times.

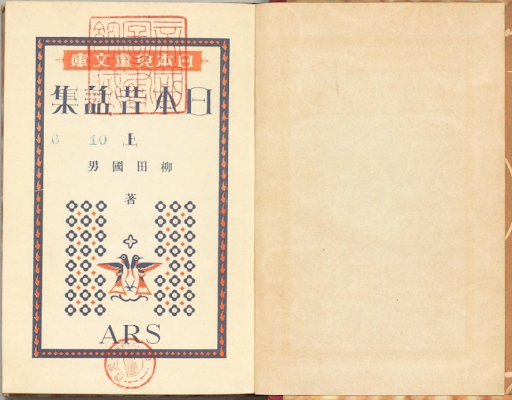

A Collection of Japanese Folktales (1930)

Much less known is a small book for children Yanagita published in 1930. It is titled A Collection of Japanese Folktales, vol. 1. The book gathers one hundred eight folktales from around Japan. Unlike his other voluminous scholarly writings, Yanagita narrates the short stories in plain language accessible to elementary school children. While there are unknown details about the publication of this book, it aligns with Yanagita’s wish to integrate the lives of commoners into history. Revised editions of this book were published in 1941 and 1960.

In the preface of the original 1930 edition, Yanagita suggests that storytelling is part of everyday life and inevitably leads to constant changes of the stories themselves. There is no definitive version of such stories and there doesn’t need to be one. Yanagita writes:

[. . .] it should not come as a big surprise that the names of people, places, tools, birds and animals, songs, and words, or even the order of events become diffetent. There is no need to think that one version or the other is a lie, or that we remembered a story incorrectly. From the very beginning, folktales are things that only a few people hear together, and later on, they are further told by one or two of them to those who are born later. There was no need to make things up, and when someone made a mistake unknowingly, there was no one to correct it either. Over the years, it is natural for these stories to change little by little, from family to family and village to village. Even if it is the same story, as people learn it and then recall it over and over again, the interesting parts of the story move forward on their own. Then, only the interesting parts of the story will be told in greater detail, and the other remaining parts may be removed, omitted, or fall apart.

Japanese Folktales for Children, p. 2.

Embracing Story Changes

I agree with Yanagita that stories, including fables, undergo changes. Over generations, it is inevitable for a story to take on a life of its own and self-develop. One important difference between Yanagita’s time and ours, however, is that it is easier for stories to cross into different spaces today, as we live in a more socially connected world. From a contemporary standpoint, we might say that different, equally authentic versions of fables are already shared in digital spaces.

This may raise a question regarding authentic voices. Having an authentic storyteller from the original culture is valuable because they can tell stories based on what they heard firsthand from their family, relatives, or the surrounding community. There is cultural significance that makes it feel different to have the story told by someone from that culture compared to someone who is not.

I believe, though, that in most cases, even if someone from another culture retells and shares a folktale, it doesn’t necessarily make it less authentic or genuine. As Yanagita seems to suggest, attempting to create a definitive, authentic version might not be suitable. Folktales are meant to be shared with others regardless of whether the narrator is from the culture or not, which is truer today than ever in my view.